Where We Work

The Clark Fork Watershed sits at the junction of two of the last remaining large and intact ecosystems — the Greater Yellowstone and the Crown of the Continent.

The 14-million-acre area spans nearly all of western Montana and a portion of northern Idaho and extends across the Canadian border to the north. The Clark Fork River begins at the confluence of Silver Bow and Warm Springs creeks, just west of Butte, Montana. As it flows northwest, it combines with the world-renowned Rock Creek, the Blackfoot River, the Bitterroot River, the Flathead River drainage, and many more.

Geology and Ecology

The Clark Fork is a gravel-bed river that rises out of heavily glaciated mountains along the Continental Divide, merging 28,000 miles of creeks and streams.

In the last ice age, glacial Lake Missoula covered this area. You can still see the varying shorelines on the surrounding mountains in Missoula Valley. Periodically, the ice dam that created the lake gave way and outburst floods scraped eastern Washington to rock and deposited fertile topsoil farther west.

The Clark Fork basin is shaped by this glacial history. Gravel-bed rivers like the Clark Fork are highly dynamic with constantly changing surface and subsurface characteristics and migrating channels. The Clark Fork and its tributaries supply some of the richest and wildest habitat found on the continent. These waterways are important to grizzly bears, lynx, wolverines, bull trout, golden eagles, elk and a wide diversity of other aquatic, avian, and terrestrial species.

Cultural History

The Kootenai, Kalispel, Bitterroot Salish, Pend d’Oreille, and Blackfeet peoples were the earliest inhabitants of the Clark Fork basin.

Tribal elders speak of the river’s abundance, including thriving bull trout populations. Deep knowledge developed over generations of observation, experimentation, and connection guided Tribal people’s subsistence patterns and way of interacting with the natural environment.* Those teachings and ways of life continue to this day.

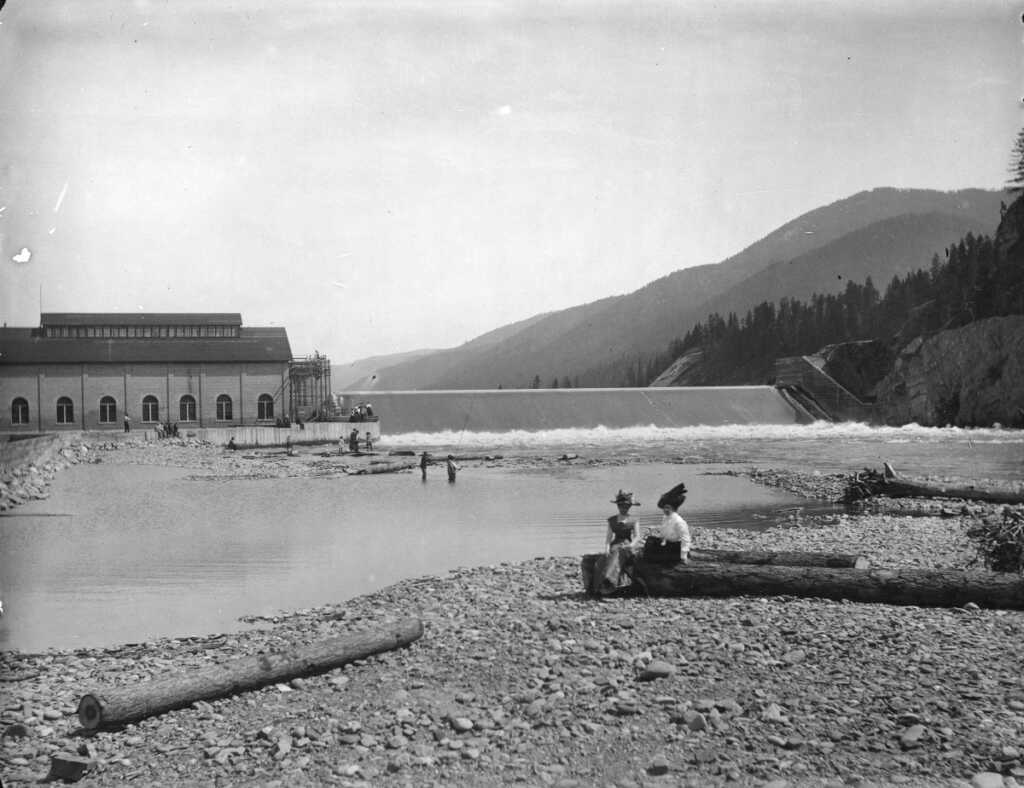

During the last century of European settlement and industrial development, the Clark Fork River was the backbone of major industries: mining, smelting, logging, pulp and paper making.

Many of these were large-scale and intensive enterprises that left a legacy of pollution and ecological damage that the Clark Fork Coalition continues to tackle.

Historic photo of Milltown Dam

The sub-basins of the Clark Fork

The Coalition addresses a wide range of challenges and works to create positive outcomes throughout the watershed. We carry out core strategies around which we have built expertise, reputation, and partnerships over the decades — particularly stream restoration, policy advocacy, and community engagement — applying them to our highest restoration and clean water priorities.

Water is life.

The Clark Fork watershed is truly magnificent in its beauty and in the waterways’ ability to sustain people, animals, plants, and the land through which it flows.